In my previous post I wrote a compiler that turns Python code into a tmux config file. It makes tmux evaluate a program by performing actions while switching between windows. My implementation relies on a feature in tmux called “hooks” which run an command whenever a certain action happens in tmux. The action that I was using was when a pane received focus. This worked great except I had to do some trickery to avoid tmux’s cycle detection in hooks—it won’t run a hook on an action that is triggered by a hook, which is a sensible thing to do.

I don’t want things to be sensible, and I managed to work around this by running every tmux action as a shell command using the tmux run command. I’ve now worked out an even sillier way that this could work by using two tmux sessions1, each attached back to the other, then using bind-key and send-keys to trigger actions.

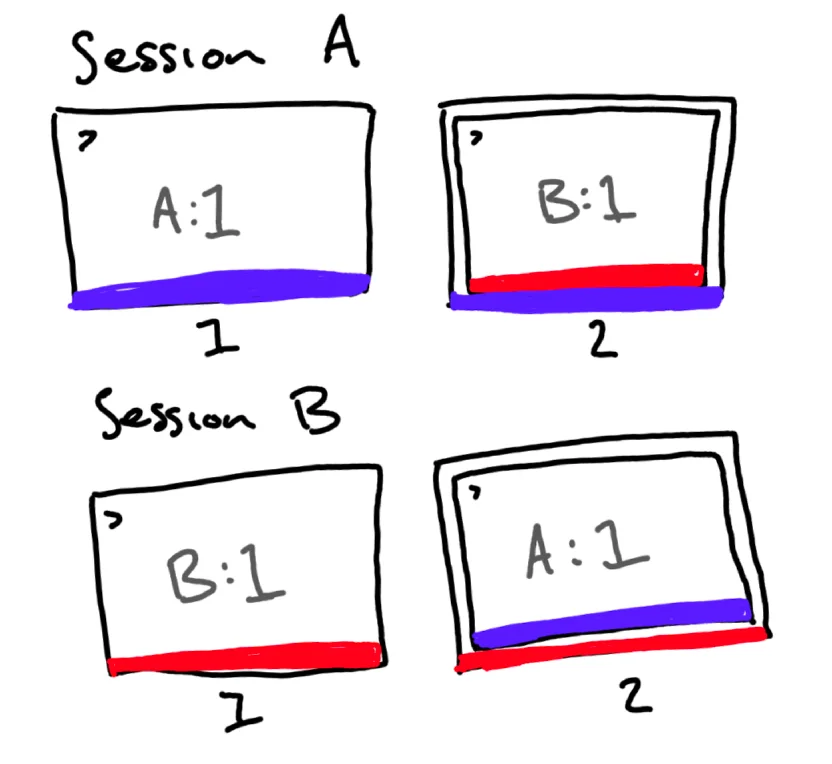

You start a tmux session with two windows. The first window just runs any command, a shell or whatever. The second window runs a second instance of tmux (you’d have to unset $TMUX for this to work). That second instance of tmux is attached to a second session, also with two windows. The first window also just runs any command, and the second window attaches back to the original session. Here’s a diagram to make this a bit clearer:

Session A (blue) has two windows, the first A:1 is just running a shell, the second A:2 is attached to session B (red) which is showing the first window in session B, B:1. Session B also has two shells, the second (B:2) is attached to session A, and is showing window A:1 from session A.

What this cursed setup allows us to do is use send-keys to trigger keybindings that are interpreted by tmux itself, rather than the program running inside tmux—because tmux is the program running inside tmux.

If you have a tmux pane that’s running a program like Vim and you run send-keys a, the character “a” will be typed into Vim. The key is not interpreted at all by the surrounding tmux pane, even if you send a key sequence that would normally do something in tmux, it goes directly to the program in the pane. For example if your prefix key is C-z, then send-keys C-z c will not create a new window, it’ll probably suspend the running program and type a literal character “c”.

However, if the program that’s running in tmux is tmux, then the inner tmux instance will interpret the keys just like any other program.

So if we go back to our diagram, session A uses send-keys to trigger an action in session B. Session B can use send-keys to trigger an action in session A, by virtue of it also having a client attached to session A in one of its panes. The program would be evaluated by each session responding to a key binding, doing an action, and then sending a key binding to the other session to trigger the next instruction. For example, using some of the tricks I described in my previous post:

bind-key -n g {

set-buffer "1"

send-keys -t :=2 q

}

bind-key -n q {

set-buffer "2"

send-keys -t :=2 w

}

bind-key -n w {

run 'tmux rename-window "#{buffer_sample}"'

run 'tmux delete-buffer'

run 'tmux rename-window "#{e|+:#{buffer_sample},#{window_name}}"'

run 'tmux delete-buffer'

run 'tmux set-buffer "#{window_name}"'

send-keys -t :=2 e

}

# ... program continues with successive bindings

The program starts with the user pressing “g” in session A, which pushes a value onto the stack and sends the key “q” to the second window, which triggers the next action in session B. That next action pushes another value and sends “w” to the second window in session B, which triggers an action back in session A. This action does some juggling of the buffer stack and adds the two values together, putting the result on the stack. It then sends “e” to the second window in session A, triggering whatever the next action would be in session B.

This should also allow the compiler to get rid of the global-expansion trick, in the last post I wrote:

Wrapping everything in a call to

rungives us another feature: global variable expansion. Only certain arguments to tmux commands have variable expansion on them, but the whole string passed torunis expanded, which means we can use variables anywhere in any tmux command.

Since we’re no longer using windows as instructions, it’s much easier to use them as variable storage. This should remove the need for storing variables as custom options, and using buffers as a stack.

The stack would just be a separate, specifically-named session where each window contains a value on the stack. To add a value, you write the desired contents to that pane using either paste-buffer to dump from a buffer, or send-keys to dump a literal value. You can get that value back with capture-pane and put it into a specific buffer with the -b flag.

Options can be set to expand formats with the -F flag, so you can put the contents of a window-based variable into a custom option with a command like set -F @my_option '#{buffer_sample}'. This would allow for some more juggling without having to use the window and session name, like I did before.

Ideally you would have a different variable-storage session for each stack frame, and somehow read values from it corresponding to the active function call. This might not be possible without global expansion of the command, but if you allowed that then you’d avoid the problems that my current implementation has with having a single global set of variables.

The astute among you might be thinking “wait Will, what happens when you want to have more than 26 or 52 actions, you’ll run out of letters!” Well, tmux has a feature called “key tables” which allow for swapping the set of active key bindings, so all you need to do is have each letter swap to a unique key table, and then the next letter actually does an action, which gives you enough space for 2,704 actions, if you only use upper and lower-case letters. But you can have as many key tables as you want, so you can just keep increasing the length of the sequence of keys required to trigger an action, allowing for more and more actions for larger programs.

I don’t think I’ve really worked around the “no global expansion” limitation that I imposed, but I think this shows there are enough different avenues to solve this that you can probably assemble something without the trade-offs that I made originally.

-

Actually you can probably do this with one session connected back to itself, but I only realised this after I’d written up my explanation of how this would work. ↩